29 Feb MUKHALINGA: SHIVA’S FACE

by Renzo Freschi

How many thousands of years ago did our ancestors realize that it is the union of the two sexes which brings about the birth, nine months later, of a new human being? Probably this outcome was seen as something supernatural, happening by divine grace, but if the god was not visible his reproductive organs were—the phallus and vagina which became cult objects. The mystery of creation is one of the most powerful archetypes in man’s history and each single culture developed it into a mythology of its own. In the Western world modern science has unveiled the myth, leaving untouched the power of instinct only. But over two thousand years ago in India this myth became religion, and the union of phallus/linga and vagina/yoni remains to this day one of the most worshiped icons in the Hindu world. Legend has it that in the course of the competition between Vishnu and Brahma as to which of the two was the Creator, a phallus of which neither of them could find the ends suddenly emerged from that boundless and timeless ocean. All of a sudden Shiva came out from a crack in the phallus, claiming to be the principle from which everything begins and ends.

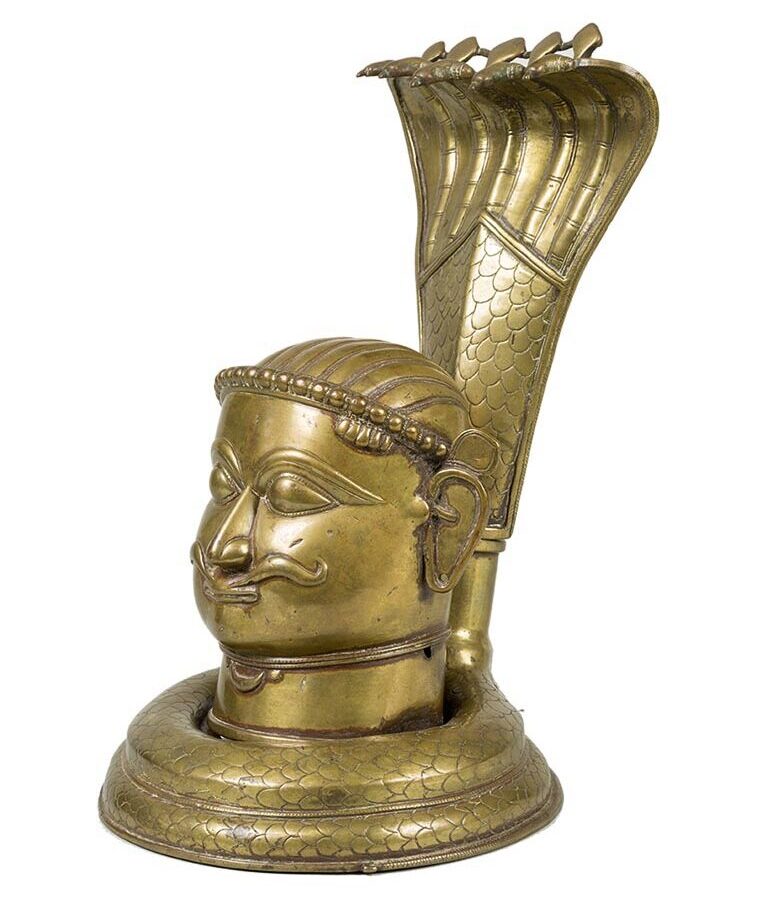

Some hymns of the Rg Veda seem to imply that a phallic cult was already practised in the early milleniums before our era, but the first example of a linga bearing the figure of Shiva dates back to the 1st century BC, that is when Hindu iconography (the representation of countless deities in their peculiar forms) was in the making. From that moment the linga with a Shiva head – the iconic form- or as a plain cylinder – aniconic form- (see photos at bottom) spread throughout India and to Hindu-influenced areas (Nepal, Cambodia, Indonesia).However, the male sex –linga– and the female one –yoni– being complementary, they were almost invariably shown united, but with the phallus head pointing up since it was considered the creative principle from which everything is cyclically born to them be destroyed or rather reabsorbed in an endless circle.For over a millenium the linga was represented both as a simple stone cylinder, sometimes with one, four or five heads, but in the 18th century, in a region of southern-central India which included Maharashtra and Karnataka, metal heads or masks to be placed upon the linga began to be manufactured, giving it a realistic human look. The characteristics of these heads are those typical of the time in which they were made, exactly as we see in coeval paintings of those regions.

These bronze and brass heads, hollow inside, have the solemn expression resulting from the intriguing union of a divine image with that of a fierce warrior. They are called mukhalinga (from mukha, face, and linga, Shiva’s erect penis) and are placed in Shaivite temples where they are worshiped by sprinkling them with ritual liquids and adorning them with flower garlands. The image below shows the function of a mukhalinga covering the phallus joined to the yoni.One of several reasons contributing to the creation of mukhalingas was to help the devotees associate Shiva’s physical aspect with the abstract one of the linga, but also to attenuate its strictly sexual meaning connected with initiation (tantric) cults of some Shaivite sects. Furthermore, in Maharashtra and Karnataka additional “local” reasons were at play, connected with certain historical facts. The Maratha empire (1674-1818) was the last Hindu bulwark against expansion of the Moghul empire—and later of the British East India Company—into Deccan. In the eyes of the populace the epic and victorious battles of Shivaji (1630-1680), the founder of the empire, made him a living manifestation of Shiva’s invincible power (in India very important figures of both sexes can sometimes be considered the avatar of a divinity).

The shape of the beard and moustache of some mukhalingas reflects contemporary fashion and the shape of the turban retained by a crown is that of Maratha aristocracy. This historic motivation—which led to a massive production and diffusion of mukhalingas in these regions—is also connected with an even older tradition, that of the “village heroes” (viras), valiant knights and defenders of the community, they too considered as local avatars of Shiva. The martial expression, the glaring eyes meant to strike fear into the enemy, the pointed battle helmet combine the qualities of a warrior with Shiva’s distinctive features—the third eye on the forehead, the small shivalinga on the crown, the cobra hood above the god’s head. The most important mukhalingas have very large open eyes meant to strengthen the concept of a god to whom nothing escapes. The pupils are incised during consecration and from then on they become a direct contact between the all-seeing god and the devotee who prays to him

Placed in large shrines and in small country temples alike, as well as on home altars, mukhalingas were made by the lost-wax casting method. Therefore they are all different and present a stylistic variety ranging from realistic to portraitural and to the stylization in the shape of a phallus.

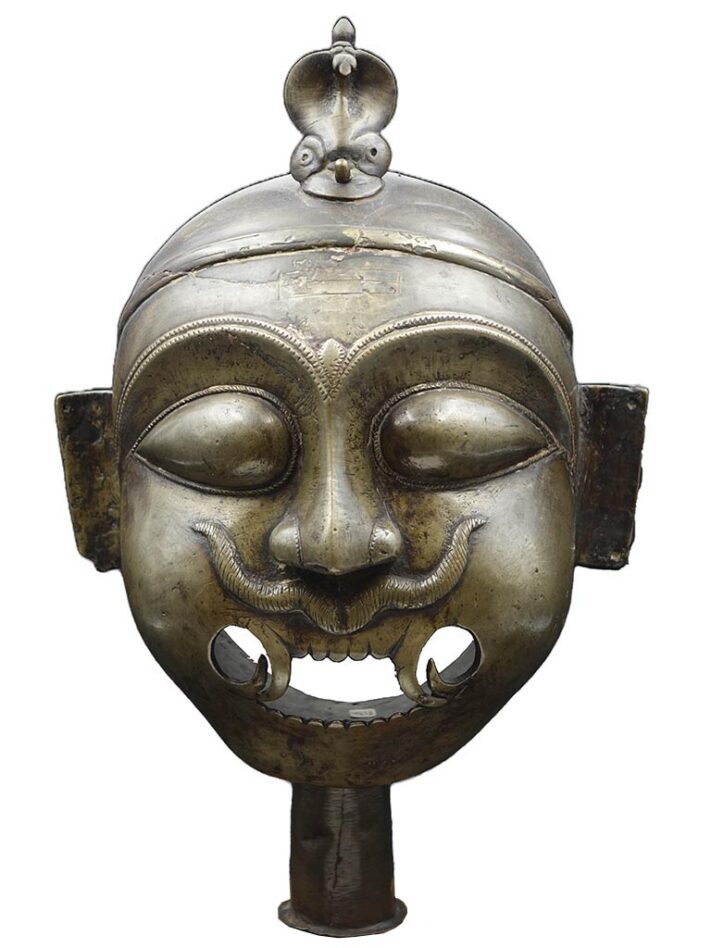

Also connected with mukhalingas were the masks of Shiva (mukhavta, i.e. heads without the rear portion) which could be mounted on the linga itself or on a wooden stand to be carried in procession spreading the gods power across the land. Simpler and cheaper to manufacture, the masks display a remarkable variety of styles, both in their sizes and expressive force.

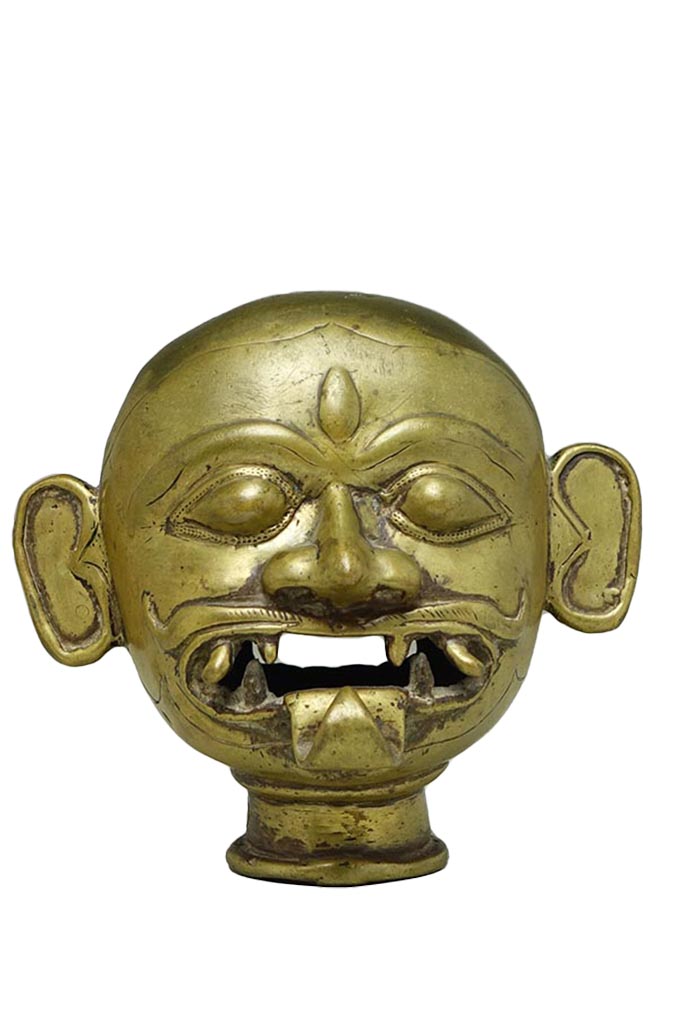

Just as the gods are there to protect man, so demons and calamities can attack him—invisible forces conceived to terrify with their looks. Thus the gods—notably Shiva— assume an even more threatening and ruthless look than the evil forces, who flee in terror when they see them. It is perhaps a simple but quite soothing train of thought which becomes manifest with the manufacture of metal heads in connection with Shiva’s cult in the same regions from which come the mukhalingas. They represent Bhairava, a wrathful form of the god which, on account of their threatening looks, were meant to protect from evil natural and supernatural forces bringing sickness and misfortune. Their gaping mouth and tongue sticking out in a hellish grimace, their teeth resembling fangs ready to tear a body to pieces, and a ghastly sneer may remind us of a theater mask, but back then they must no doubt have impressed the faithful as the frightening expression of benevolent god, but merciless against the enemies. In place of the neck they have a round support in which a pole was stuck, so that they could be carried in procession like banners clearing the way from all sorts of danger.

From the 16th century onwards, in this part of Central India (Deccan) the classical sculpture of Karnataka merged with the tribal and popular one of Maharashtra, resulting in an unmistakeable form as far as the style of the statues and the metal color are concerned. These works mainly celebrate Shiva (the protector of Maharashtra) and the knight-heroes, making them icons of a force made human, with a proud and mighty appearance.

To this day Mukhalinga, Shivalinga, Viras, Mukhavta, Bhairava still protect the Hindu faithfuls who continue to sprinkle them with flowers, powders and ritual substances as symbols of an age-old faith.

No Comments