16 Jan MAHOTSAVA THE FESTIVAL OF DIVINE CHARIOTS

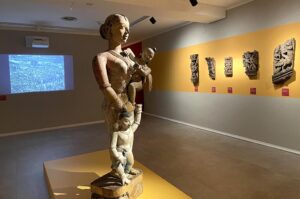

MUSEO DELLE CULTURE (MUSEC) LUGANO

Until 10th March

In the early 1980s, during a long trip across South India, I had discovered huge wooden chariots on wheels tucked away in temple courtyards or parked in the village streets. They were covered in figurative panels and I was impressed by their countless themes and fine artistry. These massive structures on wheels are pulled in procession carrying the statue of a divinity removed from the local shrine and huge crowds throng to touch the sacred architecture as if to draw on the god’s beneficial power. I had been fascinated and I had tried to find information on the tradition of the carts and the meaning of their carvings with a view to staging an exhibition on Indian wooden sculpture, but I never managed to gather enough documentation. Forty years on, visiting “Mahotsava, the Festival of Divine Chariots” curated by Indologist Giulia R. M. Bellentani, enabled me to lift a secret and make a dream come true thanks to someone else. Giulia Bellentani devoted sixteen years of her life to this research, with long stays in the places where these carts, true moving temples, are used to this day.

She had to answer the questions posed to her by the Brahmins from the Chidambaram temple in Tamil Nadu, for only those who have a certain level of knowledge of Hinduism and Sanskrit can be allowed, as on an initiation path, into the secrets and meaning of this sacred tradition. This exhibition reveals for the first time and quite exhaustively through 42 exhibits and photographs taken on site, the century-old tradition of chariots carrying the statue of a certain divinity through the village streets on the occasion of the most important religious celebration of the year.

The exhibition opens with the polychrome statues of two rampant horses placed before the chariot as if to ideally pull it. Right behind them is the statue of a coachman driving them. The horses are sometimes winged, suggesting that we are in the presence of heavenly chariots, where gods alone can dwell. All these works of art adorning the processional cart are stunningly realistic, enabling the faithful to transcend the secular world of daily life and to access the sacred and immaterial one of the deity on the chariot’s altar.

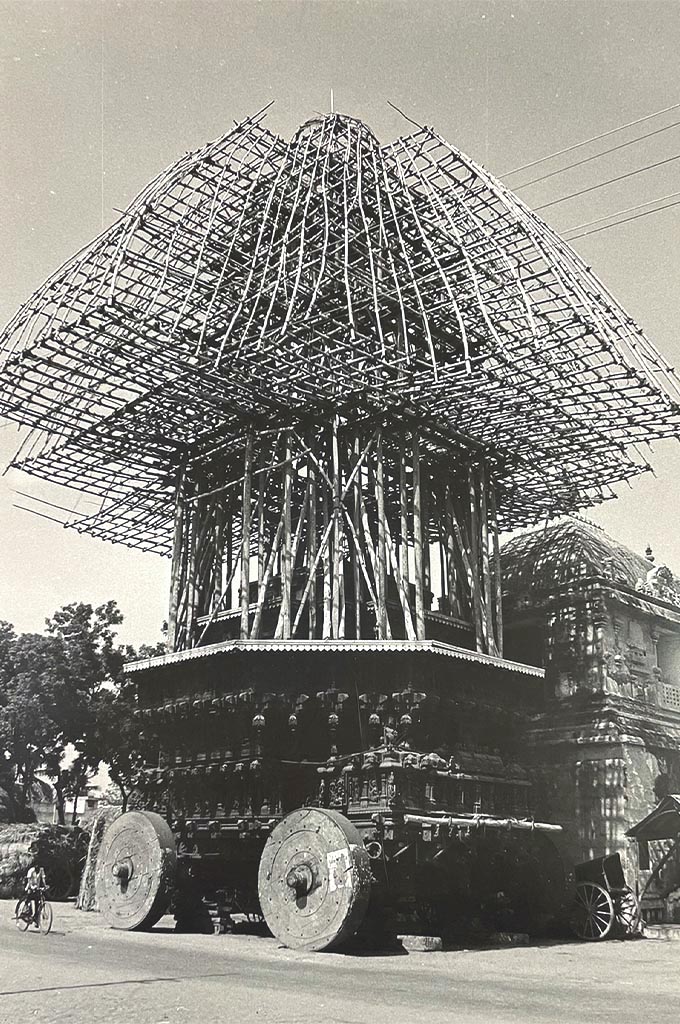

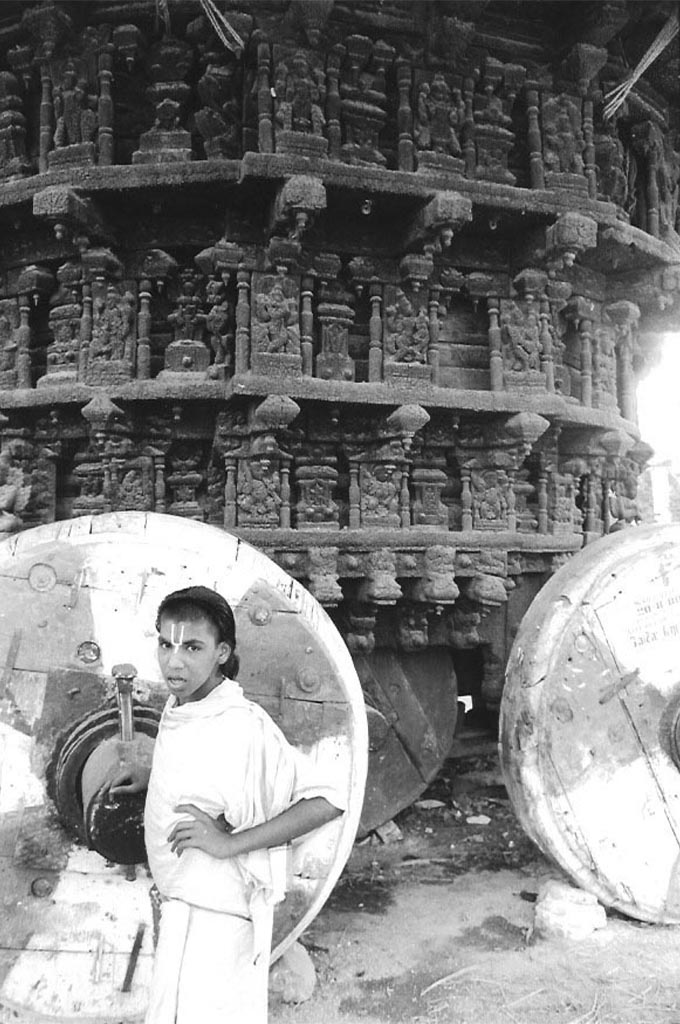

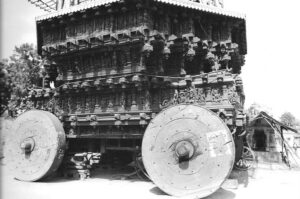

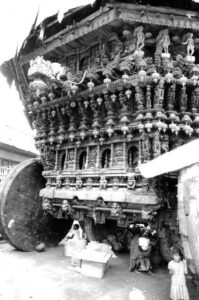

The carts are composed of two parts, the lower one resting on massive wooden wheels consisting in a high structure (a few meters) terminating in a platform carrying a pavilion—built with bamboo canes or metal tubes—lined with gaudy textiles, often painted with images of the gods. While the bottom structure is never dismantled, the pavilion is specially built in view of the procession and then disassembled. It contains an altar together with the statue of the divinity, which is considered the living, real incarnation of the god rather than its image, whereby he can send his energy towards the devotees. When the cart is not dressed for the procession it is parked along the streets close to the temple, and peddlers often use the space between the wheels to exhibit their wares, since without the statue of the god the chariot loses any sacrality.

The cart has the same structure as a stone temple and it symbolically represents the god’s universal power which emanates from inside the shrine, transported by the temple-chariot, and reaches the surrounding territory. In the second exhibition room two rare miniature models of processional chariots are displayed, giving an idea of the dimensions of the various parts.

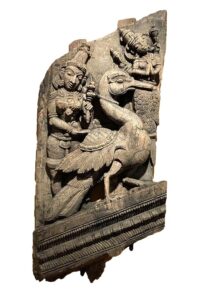

As Giulia Bellentani well explains in the catalog and in the text descriptions accompanying the visitor through the exhibition, construction of the carts, just like that of “fixed” temples, must comply with strict ritual rules ranging from the choice of the tree that will provide wood for the chariot, to the decision of the day the astrologer will indicate as favorable for starting work, to the selection of the artisans who will have to build it like true initiates and in strict accordance with the rules of sacrality. Just as the temple walls of South India are a triumph of statues, so those of the carts are covered in hundreds of panels, shelves, and sculptures featuring myriad subjects. Several show the manifold manifestations of deities standing like icons or even in action, others narrate their mythological feats, their love stories and their battles against the demons (asura), others still show fierce mythological animals which the gods have subdued and turned into proud protectors.

Some particularly long panels sculpted with great realism are true frescoes in relief telling episodes from the Bhagavadgītā.

Among the numerous items on display I was struck by some panels showing various moments of childbirth and by the extraordinary quality of other reliefs of an erotic nature, in which bodies entwined in acrobatic positions of the Kamasutra constitute true masterpieces of Indian sculpture.

“Mahotsava, the Festival of Divine Chariots” is an important exhibition in its uniqueness, the result of a long and passionate work of study and research done by Giulia Bellentani. Items from “moving temples” have at times been included in exhibitions of Indian art, but never in such a comprehensive manner as in the MUSEC.

Renzo Freschi

P.S. In this article I have included photographs of carts I shot when I discovered them more than 40 years ago, and the picture of the largest Indian ratha in Tiruvarur—30-meter high and still used—towering above a diminutive cyclist, as well as the photos by Giulia Bellentani published in the catalog. They all show that this tradition is still alive and practised by the faithful, constituting a firm basis of their faith and identity.

https://www.musec.ch/espone/esposizioni/tutte-le-esposizioni/I-carri-degli-d-i.html

Dr. Ekkehard Kaemmerling

Posted at 16:57h, 27 FebruaryDear Mr. Freschi,

thank you for your so informative and also personal essay