10 Dec Lijiang, the Naxi and the Dongba religion

by Renzo Freschi

My destination was Shangrila, the famous fictional place which the Chinese Government turned into a real geographical entity in 2001, as discussed in my article “Joseph Rock, Ezra Pound and Shangrila” on this website. However, during the journey I had decided to visit Lijiang too, one of the most popular destinations of Chinese tourism, where every year tens of millions of noisy visitors throng the small lanes of the old town, totally rebuilt in the ancient style after several devastating earthquakes.

But outside the old town local life flows to a different rhythm, like in the beautiful park where people gather in the morning to practise taichi, dancing or other forms of physical exercise. One is surprised by the general atmosphere, people are kinder than elsewhere, the town is cleaner than one would expect, and is surrounded by a nature that still seems to be in harmony with man (in the villages near Lijiang, in spite of tourism, shops and houses still coexist with crystal-clear streams and well-grown orchards).

Lijiang is the capital of the Naxi, a peaceful and “green” ethnic minority which has been living in this area for over 1400 years.

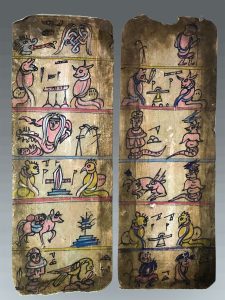

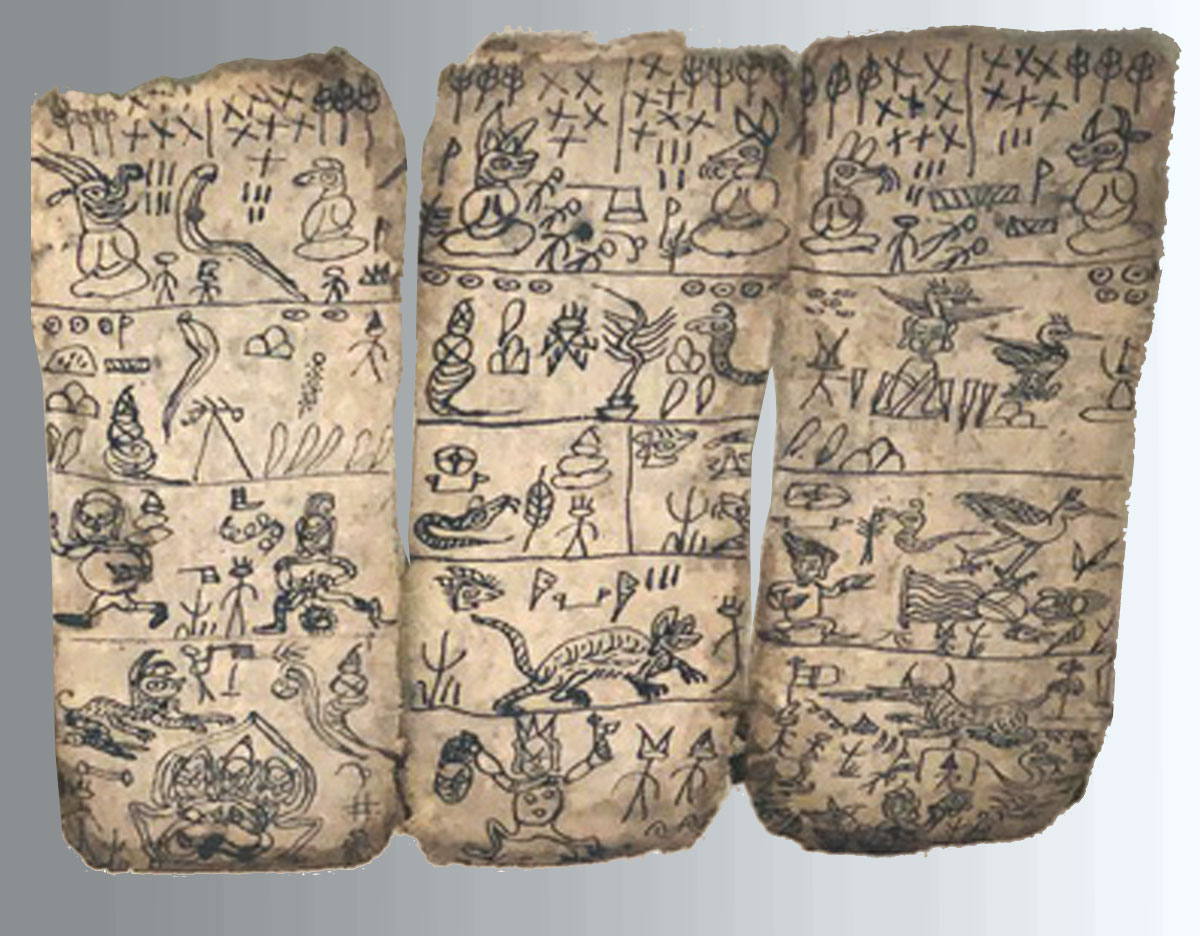

Over the centuries they preserved a curious culture with a pictographic script (hieroglyphic, one of only three in the world)

Photos from the exhibition, “Stills of Peace,the Dongba Culture”, Atri (TE), Italy, 2017

and the Dongba religion blending shamanic-animistic rituals with elements of Bon, the original Tibetan religion before the spread of “Lamaist” Buddhism.

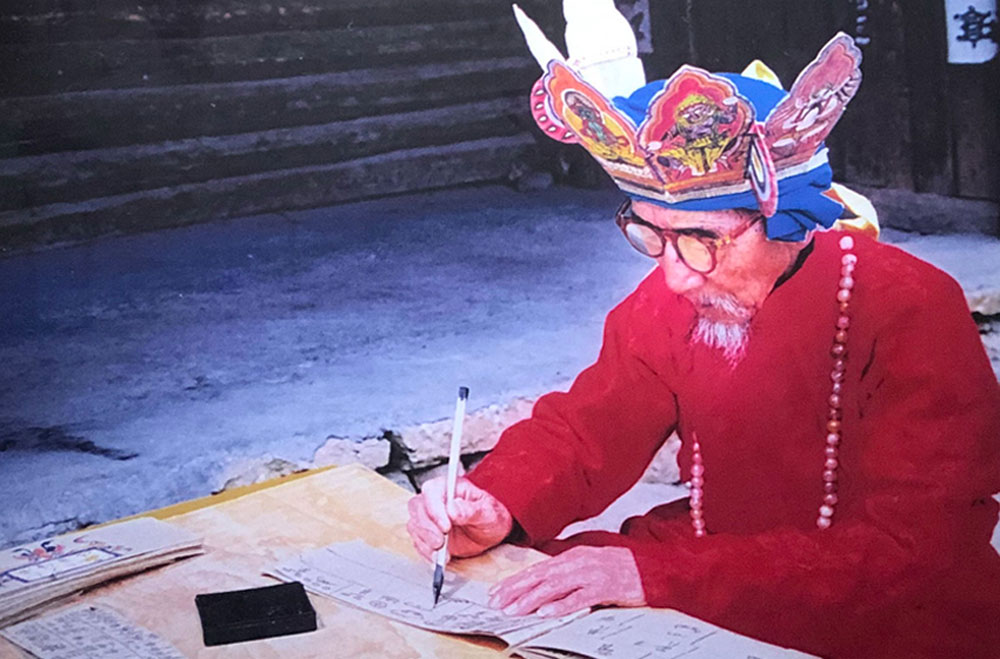

This pictographic script, still read and used by the Dongba priests (Dongba literally meaning “wise man”),

is one of the key elements of Naxi identity, in spite of the attempts made by the Cultural Revolution to stop teaching it. It is comprised of about 1400 “hieroglyphs” and has been part of the Unesco World Heritage since 1997; it is the only pictographic language still in use, since similar hieroglyphic languages, like the ones of ancient Egypt and of the Mayas, belong to the past. The writing consists of a series of signs and symbols linked in a certain sequence, read by the dongba-priest as a phonetic language. The sacred texts (more than 20,000 exist) tell the most ancient myths of Naxi culture—the birth of man and of the Naxi people, describing the complex ritual system accompanying the life of the individual and of the community. Most notable is the “Sacrifice to Nature”, a symbol of the millennial link of the Naxi with Nature. In antiquity, sacrificing to the nature god restored the harmony between man and nature in case of wrong behaviours. Even then it was believed that polluting water or making an excessive use of natural resources, such as felling more trees than necessary, were behaviours that would bring calamity and disease, hence they had to be cleansed. The combination Naxi-Nature is still so alive that Lijiang inhabitants are proud of the fact that air in the city is not polluted, and that it is the only Asian city among the ten cities in the world with the best air quality.

The Dongba Culture Museum represents the heart of Naxi identity and collects more than 10,000 cultural and literary objects—traditional costumes, items of daily use and ritual implements, books, artistic reinterpretations of the pictographic script. Some priests teach the Dongba language to students.

One room in the Museum is almost entirely occupied by a highly realistic reconstruction of a natural environment resembling a forest where an altar is placed for the sacrifice to the demon of young suicides for love, in order that their souls may leave the world of the living and go to heaven. The rite is connected with the mythical story of two young people who committed suicide because they could not fulfil their love. The story of these Naxi Romeo and Juliet is part of the literary and musical Dongba tradition and is regularly performed in theatres.

The Dongba priest is a reference figure for the whole community, he can elucidate the pictographic script and read the ancient ritual books, his behaviour constitutes an example and an ethical model for the community. Shaman, exorcist and healer, he celebrates sacrifices meant to preserve or restore the balance between the sky, the spirits and men or, through divination, to assist the faithful in taking important decisions.

When a priest dies who is particularly loved by the faithful a great ceremony is performed to dispel his karma and to enable his soul to reach paradise.

The Dongba priest wears Chinese-style ceremonial robes but a Tibetan five-pointed crown with the Buddha at centre and the four guardians of the directions on either side.

In some rites he wields a carved wood ritual dagger quite similar to that of Tibetan lamas and Nepalese shamans.

The Naxi social structure is believed to have remained matriarchal for centuries, only later to be modified into the traditional Chinese monogamic family. However, a matrilineal tradition has survived whereby the newborn baby takes the mother’s family name.

Through the pictographic script and the strong presence of the shaman-priest, the Dongba religion has miraculously preserved the memory of archaic cultures and of animistic traditions still quite detectable in ritual practice to this day, despite the Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian influences which were grafted onto the original structure.

No Comments