09 Mar NEPALESE TRIBAL MASKS DISCOVERY AND ADVENTURE,

by Renzo Freschi

To the friends with whom I had the luck of making a discovery and then turning it into an adventure.

1971:BY BUS TO KATHMANDU In 1971 I reached Kathmandu, the end of a land journey that began from Europe to Afghanistan, then to India and finally to Nepal. I was a young merchant and had taken an interest in ethnography and folk art, and was shuttling between Milan and the Orient. I traveled by train and bus among common people and from their costumes and jewelry I learned to identify their ethnicity. Upon arriving in Kathmandu the scene and atmosphere struck me as what 16th-century Florence must have been like: a city, no—a valley, where the eye was lost among pagodas, temples and palaces decorated like works of art. Every morning the main square of Basantapur teemed with sellers of ancient marvels, jewelry, wood carvings, masks, furnishings, ritual objects, illuminated books, sacred images—all waiting to be exchanged after some haggling which was both a ritual and a way to know the person in front of you. The articles were mostly Nepalese but there were also Tibetan ones from the diaspora that brought a sizeable community to the valley, and with the migration everything the Tibetans could rescue or obtain through mysterious ways.

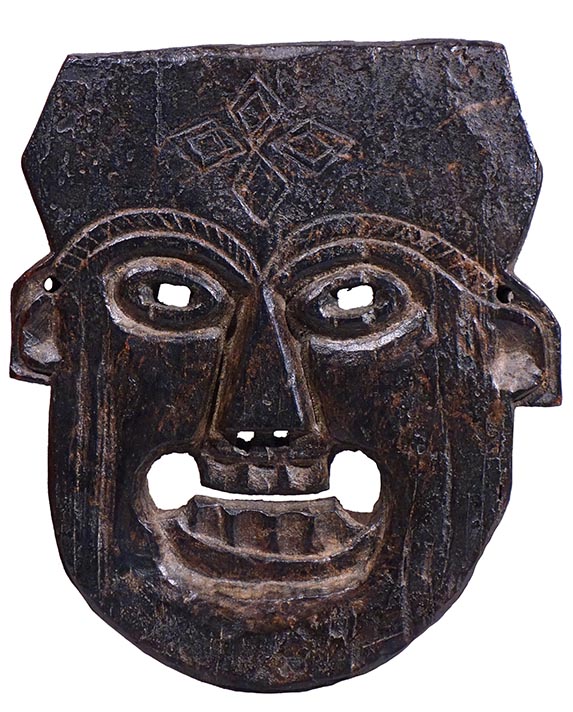

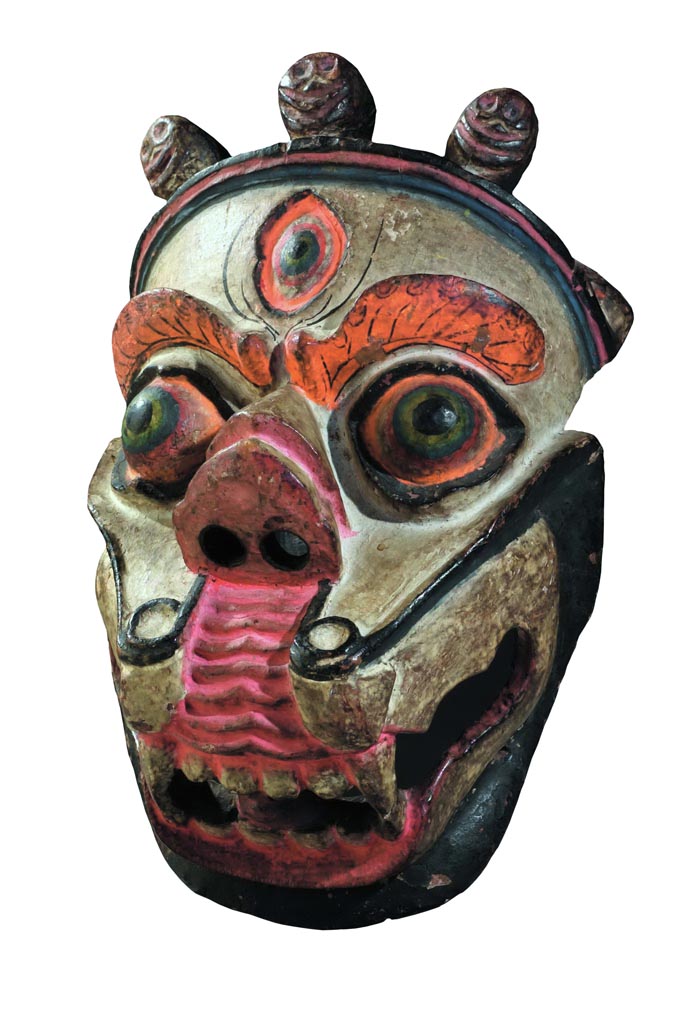

1975: A MYSTIFYING DISCOVERY After the mid-1970s, in that square and in local shops, more masks appeared alongside the “classical” ones from Tibet. These masks were completely different, covered in hair, with extraordinary shiny patinas supporting fierce or dazed expressions; sometimes they were made of roughed out pieces of wood. No-one knew or was willing to reveal where they came from. Possibly these odd masks had been discovered by some local supplier while going from one village to the next to supply antique dealers and markets. So old were they that even their owners had lost all memory of them. The first merchants of these peculiar masks were the Nepalese on the square, soon to be surpassed by the Tibetans who were always unrivaled traders. They sniffed out the business and opened a host of shops behind Freak Street, where one also wandered for a chat and for the pleasant company. Tsering Tashi, Pasang, Rinchen, Dawa, are all people still holding a place in my heart. There was also Karma Lama, who opened the Ritual Art Gallery, just a stone’s throw from the Royal Palace. He sold masks at such exorbitant prices that only the wealthy tourists could afford them.

SHAMANS AND DRUMS Around this time I had an otherworldly encounter. It was morning and I was on the outskirts of town. I heard the sound of drums coming from afar. It was loud and rhythmic—first the beats were fast, then they slowed, and then they picked up again. But these were not the drums I was used to hearing in the evening when devotees sang for the gods in the temples. I tried to locate where that hypnotic rhythm came from, and at last I saw them: seven or eight men in white cassocks that reached down to their feet, sacred seed cords tied across their chests and a crown of colorful feathers on their heads. This parade moved to the beat of the drums with the celebrants seemingly in a trance. This was my first encounter with shamans.

THE SHAMANS’ MASKS? At the time I was in the habit of seeing Piero Morandi, a brilliant discoverer of unknown treasures and the mentor who introduced me to Indian and Nepalese folk art. I was also in the company of Éric Chazot, a scholar of the Nepalese world who became a successful writer. In the evening we would meet in excitement to look at the masks we just purchased and to fantasize about shamans wearing them during their trance to fight off the hostile forces of nature, the evil eye, and witches. Masks and shamans were a perfect combination, a magic formula that made us feel like a new breed of Giuseppe Tuccis or Sven Hedins. It was 1977-1978 and our fantasy was only matched by our ignorance; at that age dreaming is much more pleasant than knowing.

In those years hippy communities that formed in Kathmandu freely followed their inclinations in spirituality, art, business, drugs, and treks. Among them was a group of Italians who coalesced around Piero Morandi, while the French aligned with Éric Chazot. There was also a considerable number of Americans, including Ian Alsop, who was destined to become a renowned expert of Nepalese art and culture. From this motley crew a true hunt for primitive masks would begin that aimed at both acquiring the best artifacts and identifying their origin. This was the real beginning of the story and of the business of buying and selling Nepalese masks, but first a personage appears…

1975: THE STORY BEGINS As early as 1975 Fausto Doro, a fearless traveler-adventurer from the Italian city of Turin, brought the first Himalayan masks to Italy. At that time collectors were predominantly attracted to Tibetan masks that were endowed with a powerful charm and represented harbingers of a world not yet known to the large public. But Doro had an eagle eye and was ahead of his time.

A couple of years later, in a collection of daring politico-philosophical conjectures called Il Primate a Stazione Eretta I, (The Upright Standing Primate I) he included photographs of a second set of masks, some of them clearly primitive. It was 1977 and Doro legitimized on printed paper the existence of masks “like the African ones”, as we used to say.

1978: ANTHROPOLOGISTS, SCHOLARS, JESUITS Back in Kathmandu, the question, “Do shamanistic masks exist?” continued to be debated and remained unsettled. In 1978 I turned to the academic world to find the answer. I took my courage in both hands and arranged to meet Dor Bahadur Bista, the prominent Nepalese anthropologist and author of People of Nepal, the first book on Nepalese populations and ethnic groups. At our meeting at Kathmandu University Bista looked down at the well-groomed but Indian-dressed and clearly hippy young man, betraying his strong prejudice. He looked distractedly at my photos of the masks and casually dismissed me saying he had never seen anything like them. I also met Michael Oppitz, a German ethnologist who later became the director of the Ethnographic Museum in Zurich. For years Oppitz had been researching the Magar in a remote area of northern Nepal. He too said he had never seen such masks. Lastly, I consulted two American researchers dealing with language and family structure of the Nepalese society, going away with the same result.

I was discouraged; however, just at that time in 1979 Faith-Healers in the Himalayas by Father Casper J. Miller was published. Miller was a Jesuit priest living in Kathmandu who had witnessed and documented shaman ceremonies from various ethnic groups. His book quickly became the standard reference for those interested in the subject, and it was a true inspiration to me. I decided to ask the shamans themselves if and when they wore these masks, thus I organized two mountain treks in order to interview them and to attend an important festival.

In my second trek in 1981 I climbed to the top of Kalingchok, a 3850-meter high mountain in central Nepal where lots of shamans from the region had gathered to celebrate their tutelary deity. To be surrounded by singing and dancing shamans in a trance was an extraordinary experience, but there was still no trace or confirmation from the shamans I interviewed of a shamanistic use of masks. I went back to Kathmandu convinced that I had solved at least part of the mystery: shamans do not wear masks! The question I had asked in the beginning of this story had been answered and I decided to leave it to others to further research the meaning and origin of Nepalese primitive masks. I continued to take an active interest in Nepalese primitive art for a few years, then—while still keeping contact with this world—my professional interest slowly shifted towards classical Asian art.

1975: THE FIRST MASKS IN THE WESTERN WORLD Meanwhile the first primitive masks began to arrive in the West from two main sources. The first was Europe, mostly from Paris and some from Brussels. The second source was the U.S., San Francisco mainly and New York City marginally. But why were the market and the collecting of Nepalese “primitive” art concentrated in these cities rather than distributed around the world as was the case for “classical” Oriental art, for which beautiful museums had been in existence for a long time?

Helped by Picasso, cubism, and the discovery of “black” art, almost a century earlier in Paris, primitive arts had come out of the avant-garde and into the museums and consciousness of a wide public.

It is reasonable to believe that this awareness aroused a special curiosity for these masks among the young travelers who were arriving in Kathmandu. It was this orientation, and the fascination for discovering something unknown, that led to the birth of galleries and collections of Himalayan primitive art.

It is equally interesting to revisit the reasons leading to the creation of such a market in California. The mind turns to the Beat Generation and the caravans of hippies on their way to India. At the end of the 1960s alternative culture was already quite popular among the youths of San Francisco and New York, and the hippy movement had created a pervasive sensibility for Oriental art and culture.

1975-1980: CALIFORNIA – HIPPIES, DEALERS AND MARKETS Between 1975 and the early 1980s masses of young people returning from the Orient began to sell, either privately or on the markets of the San Francisco Bay area, the objects they purchased in India and Nepal. Vicki Shiba, John Stewart, Robert Brundage and Bruce Gordon (who found his first mask during a trek in Nepal) were among the first to introduce primitive Himalayan art to California. Accompanying them were Tony Anninos, Bruce Carpenter, James Willis (who in 1972 opened an African art gallery) and Thomas Murray, a specialist in Indonesian art and masks who would later be appointed as a member of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee by President Barack Obama. Some, such as Jeremy Pine, shuttled between the West and Nepal; others, like Tom Cole and Bruce Miller settled down and operated in Kathmandu where Ian Alsop also lived. It was a composite community with many originating from the hippy movement and subscribing to an unconventional way of life matched with a real interest for the local culture. Others were art and antique dealers already, still others were captured by the fascination of unknown objects.

Mort Golub was one of the latter. In 1985, at the Sausalito flea market, he bought a mysterious black mask that had just arrived from Kathmandu. As he himself recounted in an amusing article published in Arts of Asia, he had to keep the mask in a drawer because it frightened his daughter. Despite the fact that Thomas Murray, when asked his opinion of the mask, offered him four times the price he had paid, Golub decided to keep it. With that mask he established, with the help of Murray, one of the first collections of Himalayan masks. The mysterious power of these masks was an influential force in Golub’s creative work. To this day he still manufactures masks made of various old materials joined by traditional methods which often seem to be animated by the same “archaic and shamanic” spirit as the original ones (page 28).

On the other coast of the U.S., in New York City, Himalayan tribal art also had its enthusiasts including Moke Mokotoff, Arnold Lieberman, Maureen Zarember of the Tambaran Gallery, and Joe Gerena, an eclectic and competent merchant who many years later would organize an exhibition of masks from all over the world—ancient and modern, rare and extraordinary, fanciful and bizarre.

1981: PARIS, ADVENTUROUS PIONEERS The Paris community of dealer-travelers was less numerous than in the U.S., but it had the advantage of operating in an environment where interest in non-European arts, and Oriental art in particular, had been alive for a century. Éric Chazot, Jean-Pierre Janykian, and Michel Lostalem were the first to bring back primitive masks from Nepal. They were then joined by François Pannier, Christian Lequindre, Jean-Luc Cortes and the Daffos-Estournel Gallery.

In 1981 Jean Jacques Porchez organized at the L’Île du Démon gallery, specializing in Indonesian art, the first exhibition entirely

devoted to Nepalese primitive art. Art Tribal du Nepal presented shaman ritual objects, musical instruments and a considerable number of masks which the catalog endeavoured to place in a specific cultural and religious context. One of the essays (Art et Chamanisme au Nepal) was written by Éric Chazot under the pen name Patrick Pevenage. Chazot was set to become the dean of Nepalese tribal masks. The exhibition at the L’Île du Démon—the very center of primitive art galleries in Saint Germain—stirred quite an interest for never-before-seen objects. It was in those years that Josette Shulmann, Marc Petit, Max Itzikovitz, Alain Bovis and Michel and Liliane Durand-Dessert began their collections. In parallel the market picked up in Brussels thanks to Dominique and François Rabier, Jean-Pierre Jernander, Sylvie Sauvenière and later Joaquin Pecci.

devoted to Nepalese primitive art. Art Tribal du Nepal presented shaman ritual objects, musical instruments and a considerable number of masks which the catalog endeavoured to place in a specific cultural and religious context. One of the essays (Art et Chamanisme au Nepal) was written by Éric Chazot under the pen name Patrick Pevenage. Chazot was set to become the dean of Nepalese tribal masks. The exhibition at the L’Île du Démon—the very center of primitive art galleries in Saint Germain—stirred quite an interest for never-before-seen objects. It was in those years that Josette Shulmann, Marc Petit, Max Itzikovitz, Alain Bovis and Michel and Liliane Durand-Dessert began their collections. In parallel the market picked up in Brussels thanks to Dominique and François Rabier, Jean-Pierre Jernander, Sylvie Sauvenière and later Joaquin Pecci.

In 1984 after a few trips to India and Nepal, François Pannier opened his gallery Le Toit du Monde specializing in Himalayan tribal art which still operates today. A few months later, on the occasion of Pannier’s exhibition of animal masks (Masques Animaliers), Jean-Christophe Kovacs, passing by the display window, was captivated and immediately purchased a mask. Since childhood Kovacs had taken an interest in Tibet. He filled his library with books about India and the Himalayas, but he had no idea where this passion came from. Only after he started his collection did his parents reveal to him that one of his ancestors was Sándor Kőrösi Csoma (1784-1842), a Hungarian explorer and orientalist considered the father of Tibetology and the author of the first Tibetan-English dictionary and grammar. The reader is free to believe in the chance nature of this relation, but since rebirth is one of the tenets of Buddhism, it is too tempting to surrender to the fascination of an astral coincidence! Kovacs was mainly a passionate ornithologist who was used to exploring the land in order to classify birds. After acquiring a certain number of masks he decided to visit the Himalayan countries with his brother Yvan for ornithological research but also to scientifically classify masks, ceremonies and environments the two of them would encounter in their treks. It was the beginning of a long adventure which, through 25 trips across the entire Himalayan sweep, enabled the Kovacs to have an extraordinary experience on the field and to put together an archive of some 50,000 photographs.

THE ITALIANS AND HIMALAYAN MASKS

In Italy, after Fausto Doro’s solitary adventure, a small group of merchants came together to try to bring Nepalese primitive art into a milieu that was fairly impervious to novelties. In 1978 I hosted an exhibition of Tibetan masks in my former Mandala Gallery, and in 1984 I approached the CRT (Centro Ricerche Teatrali) with the idea of organizing two exhibitions in Milan on shamans and Nepalese primitive masks, both were jointly curated with Éric Chazot. In 1996 Angelo Attili, a merchant of Asiatic art in Parma, opened the exhibition Alle Radici delle Religioni Tibetane (At the Roots of Tibetan Religions) at the Galleria Akka in Rome, showcasing Nepalese objects and tribal masks. Lastly, at the end of the 1980s Roberto Gamba, photographer and dealer in primitive art, sold to Luciano Lanfranchi the mask shown on the cover of this book. It was the first mask in his collection, and thus began Lanfranchi’s journey in the world of Himalayan masks.

More recently in Italy, Gian Marco Matteuzzi became intrigued by Himalayan primitive art after reading Giuseppe Tucci’s books and traveled to India and Nepal. In 2008 he created ethnoflorence, the first non-commercial website for Asian tribal art. Gradually the website became the place where everything occurring in this milieu was posted—exhibitions, books, photo reports, news and a constantly updated newsletter. Through the years Matteuzzi built up a large digital database accessible on-demand to interested parties.

1988: PARIS – THE FIRST PUBLIC EXHIBITION Back in Paris, in 1988 François Pannier’s gallery, Le Toit du Monde, became the standard reference for anthropologists and collectors of things Himalayan, and the monographic Lettres du Toit du Monde were esteemed for their academic quality. Hence Pannier was tasked by the State Administration (EPAD) to organize the public exhibition Masques de l’Himalaya du Primitif au Classique in the rooms for cultural activities of the Défence in Paris. On show were 93 masks from private collections, and the catalog included two essays, one by Marc Petit, a writer and collector, and the other by the already famous Éric Chazot.

1989: USA – FACING THE GODS At the same time in the U.S. Lawrence Hultberg, a gallerist in San Francisco, and Éric Chazot presented their project for an exhibition of Nepalese primitive masks to the most prestigious American cultural and museum complex, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. His proposal was accepted and Facing the Gods: Ritual Masks of the Himalayas, curated by Hultberg and Chazot, was presented from 1989 to 1991 in seven museums among five American states, spanning from Hawaii to Florida. On display were 75 masks from American and European museums and private collections along with large-format photographs of Himalayan scenes.

These global exhibitions marked the turning point for Himalayan primitive art which shed its long-associated aura of exoticism and acquired an undeniable ethnological and artistic value. Obviously the great success of these initiatives prompted many private galleries to organize themed exhibitions: Dave DeRoche in San Francisco, the Met Life Gallery in New York and also in New York the Pace Gallery, which for quite some time had added a Primitive Art section to the historical Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art.

Numerous magazines including Tribal Art began to publish articles on this subject. In 1995 Hali published “Demons and Deities”, a lengthy article by Thomas Murray on Mort Golub’s collection of masks. The article was important for it presented a number of top-quality masks and set them in their historical-cultural context.

NEW COLLECTORS New collectors sprang up such as Sam and Sharon Singer, who turned their house in San Francisco into a museum of primitive art with numerous Himalayan works. In Spain Eudald Daltabuit curated the Pons Collection in Barcelona, and in the same city Gustavo Gili and Rosa Amoros started their collection which would be published in 2005 in Énigmes des Montagnes. Masques tribaux de l’Himalaya with two prefaces by Eudald Daltabuit and François Pannier.

Marc Petit, a Parisian artist and literate who had been collecting primitive art since the 1980s, bought his first Nepalese mask in 1981 and decided to set off for Kathmandu with a view to learn more about the environment of these masks. This was the start of a collection which Petit presented in 1995 as a beautiful volume titled À Masque Découvert: regards sur l’art primitif de l’Himalaya in which 120 superb masks were presented and interpreted by Petit with a poetic, often surreal, sometimes even far-fetched approach. À Masque Découvert proposed, or rather imposed on Himalayan mask collecting, an aesthetic approach that could no longer be ignored.

One would imagine that all these exhibitions, articles, books, and new collections would sanction a consolidated, if not growing, success for these masks. Instead, after 1995, the situation inexplicably reverted to a normal routine that barely allowed the market to survive without anything dramatically new. It would take another ten years for interest in this field to resurface, like a stream re-emerging from a karstic sinkhole, and to finally reach a stable condition. However, this pause was badly needed, for the questions raised in the beginning of this story—where do these masks come from, whom do they represent, when are they used—had only been partially answered up to that point.

RESEARCH AND DISCOVERIES IN THE NEW CENTURY

Thus began years of field research, jungle treks and expeditions to godforsaken valleys and villages clung to mountain slopes, trips among communities who jealously guarded their traditions and others that were too eager to accept modernity with inevitable consequences. Those former young people who discovered the masks and now tried to solve their secrets among forests and mountains were at last joined by anthropologists and researchers who were also interested in material culture, folk festivals, and ancient rites. Along with Éric Chazot, Christian Lequindre, Jean-Luc Cortes and the Kovacs brothers, numerous anthropologists undertook specific field research.

In the following years many of them would also provide assistance for exhibitions, such as Mireille Helffer, Dominique Blanc, Bérénice Geoffroy-Schneiter, Gérard Toffin, Pascale Dollfus, Gisèle Krauskopff, Christophe Roustan Delatour and Anne Vergati, who published a book about masks of the Kathmandu valley. This articulated collaboration finally established a liaison between the academic world and the market which enabled a free flow of information for everyone’s benefit.

As we already noted, Kathmandu was the “capital” of Himalayan masks from the very beginning, but the different types of masks did not reach the Tibetan and Nepalese dealers all at the same time. We could say that they arrived in waves linked to the discoveries made by those who went about the villages in search of new artifacts. There was almost never direct contact between these searchers and the western buyers: the filter of local merchants was virtually impenetrable. It is also because of this mistrust that for a long time it was impossible to know where these masks came from and to have any clue as to their meaning and use.

As Jean-Christophe Kovacs suggests, masks from the Tibetan tradition and from Kathmandu were the first to arrive on the market between 1970 and 1980, followed a few years later by the Monpa and Sherdukpen masks brought by Buddhist pilgrims who came from the Eastern Himalayas to visit the shrines of the Kathmandu valley. The “discovery” of the Western Nepalese masks and of the wooden statues photographed many years earlier by Giuseppe Tucci (Nepal: The Discovery of the Malla) only happened in the late 1990s. In the 1980s and 1990s masks from Himachal Pradesh and from nearby Indian regions could be found in New Delhi, and often in Kathmandu as well.

2007-2009: FRANCE – MASKS, EXHIBITIONS, MUSEUMS In 2007 François Pannier, who had become by then the link between the academic world and the market, organized three simultaneous exhibitions at the Mairie du VIe Arrondissement in Paris—on Himalayan masks, the shamans of Nepal and carved wood implements for butter production (ghurras) in some Nepalese valleys. The last topic was particularly relevant because it demonstrated how interest had expanded to include new aspects of the Himalayan folk art of these regions.

Meanwhile Pannier inaugurated a two-day seminar (Colloque International sur les Masques et Arts Tribaux de l’Himalaya) with the participation of both French and Nepalese scholars at the Cernuschi Museum, the Asian Art Museum of the City of Paris headed by Gilles Béguin, the well-known scholar of Oriental art.

The year 2009 was pivotal in this storytelling. Christophe Roustan Delatour inaugurated at the Musée de la Castre in Cannes, of which he is the current deputy director, the section on Nepalese shamanism with some tribal masks. Roustan Delatour had been exploring the Himachal Pradesh since 1995 and was by then one of the foremost experts of phagli festivals in the Kullu valley (see pages 49-67), so much so that his photographic archive comprises more than 300 masks.

Also in 2009 Népal, chamanisme et sculpture tribale by Marc Petit and Christian Lequindre was published. Lequindre had arrived in Nepal in 1976 purely on a personal spiritual Buddhist quest, but on the day he was due to return to France a family of Bhutanese refugees entrusted him with some carpets and paintings to sell in order to use the earnings for their livelihood. A few months later Lequindre returned to Kathmandu to give them the money and began to establish an interest in primitive masks. The first items he purchased were a fish-mask, made from the fish itself (pp. 238 and 239) and a mushroom-mask, fashioned from a real mushroom (No. 215). Both masks are now in the Lanfranchi collection. Between 2000 and 2005 Lequindre made four trips to different districts in Nepal. These explorations were particularly hard due to the scarcity of food and they were hampered by complex environmental and social issues. Nevertheless, he managed to document and film some masked festivals and ceremonies, which he collected in a DVD and was included with the 2009 volume co-written with Petit. This book was another piece of the large puzzle of Nepalese masks.

The year closed with the most important exhibition of Himalayan masks ever staged in Europe. Curated by François Pannier at the Bernard et Caroline de Watteville Foundation in Martigny, Switzerland, Masques de l’Himalaya presented 143 masks from public and private European and American collections. The catalog was a state-of-the-art snapshot clarifying the connection between masks and folk festivals and focused on the difficulty of arriving at a geographic and typological classification.

In 2010 and 2011 two exhibitions on the Durand-Dessert Collection opened one after the other in Paris, the first one curated by François Pannier and the second by Éric Chazot. Michel and Liliane Durand-Dessert formerly operated an avant-garde art gallery and they had been collecting African art for many years. Attracted by a style and aesthetics that were completely different from the canons of “classical” primitive art, in 1987 they acquired their first two Himalayan primitive masks. Their astounding collection included masks and sculptures from all of Nepal. In 2008 Chazot himself set out for Humla, a region of north-western Nepal bordering Tibet, with the task of investigating the masked dances of the Byanshi which was later published in the magazine Sciences et Avenir. During the expedition the steep mountain track suddenly slid away, plunging Chazot and his horse down the ravine to the bed of the Karnali river. Seriously hurt, with six broken ribs and a broken vertebra, he was unable to move for hours until, from the track high above him, somebody saw and rescued him. It is tempting to believe that Chazot was protected by Ban Jhankri, the primordial shaman worshiped by all Nepalese shamans. During rehabilitation he worked on the two volumes about the Durand-Dessert collection with his account of the several trips he made in all of Nepal. Chazot managed to link some type of masks with the ethnic group they belonged to, and to find out on which occasions they were used.

2010: THE MUSÉE DU QUAI BRANLY In 2010 another crucial event took place in Paris. Marc Petit donated 25 masks from his collection to the Primitive Art Musée du Quai Branly which were then shown in the exhibition Dans le blanc des yeux. It was an important event because, as the Director Stéphan Martin explained, “With this donation the Museum plays a precursor role, since at this time it is the only Nepalese primitive mask collection in a public French institution. We believe the time has come to make these fascinating masks accessible to the public…” As he already did with his 1995 book, Petit put forward his aesthetic vision as a guideline. At long last, thanks to the collaboration between the collector and the museum, Himalayan primitive art became part of the large family of “Art premier.”

Even the world of classical primitive art, which had always maintained a very prudent attitude towards Himalayan primitive art, owing to the difficulty of assessing it with its traditional canons, started to look at it with more interest. In 2010 Renaud Vanuxem, an African art gallerist in Paris, displayed a set of Nepalese masks in collaboration with Marc Petit and in 2012 Alain Bovis’s gallery organized Masques de l’Himalaya, le primitivisme sauvage. Bovis, a collector and later a dealer in African art, began to buy masks in the 1990s because he was “charmed by their wild but deeply human strength.” He believed the time had come to include Himalayan works in classical primitive art collections.

Starting in 2010 he presented in his gallery four exhibitions on Himalayan masks, one after the other. The last one, in 2013, was dedicated to the collection of Bruno Gay, an eclectic collector in Paris. Simultaneously in Brussels, Joaquin Pecci opened an exhibition of Nepalese masks.

Big auction houses also began to include these masks in primitive art sales, and in 2014 Sotheby’s sold a Magar mask in Paris for € 43,500.

In the last few years interest in Himalayan primitive art has strengthened and many galleries now regularly show a number of these works.

Besides the historic gallery owned by François Pannier, one of the most active ones is that of Frédéric Rond, a young Parisian dealer of old Asian art, both classical and primitive. In 2015 Rond organized Himalayan Tale, featuring masks from international private collections. More exhibitions took place in Helsinki, New York, San Francisco and Sankt Galle.

LATEST RESEARCH Lately, field study and research have provided a more detailed, although still incomplete picture of Himalayan tribal culture. In 2014 Mascarades en Himalaya. Les vertus du rire by ethnologists Pascale Dollfus and Gisèle Krauskopff was published. The volume is a compilation of results from expeditions to various Himalayan regions with photographs dating from the end of the 19th century to current times and also documents the use of some types of masks in their setting. To the masks were added wooden sculptures from Western Nepal, studied on site for many years by Jean-Luc Cortes and also featured in Max Itzikovitz’s collection. Wood Sculpture in Nepal, Jokers and Talisman, written by Itzikovitz and Bertrand Goy, not only provides a brilliant introduction to Nepalese primitive art but also showcases a beautiful selection of masks.

The latest studies—such as the research and the documentary films that Adrian Viel and Aurore Laurent have been producing for many years—have ruled out the possibility that Nepalese shamans wore masks, but the association of shamans to masks has unfortunately become a difficult-to-eradicate vulgate. In the exhibition Becoming Another, organized by the Rubin Museum in New York and curated by Jan Van Alphen, the captions for some Nepalese masks read “Possible Shamanic Mask” even though the relevant text states that no evidence exists of Himalayan masks worn by shamans; however, this does not detract from the quality of the pieces selected by Van Alphen.

The origin and use of some types of masks is no doubt clearer in light of the latest research and publications. Many are ritual or ceremonial, others are used in folk theatre, some have an apotropaic function, and others give a face to spirits of nature, forebears, and the dead. Most of them are worn on the face, but some are simply laid on the ground or hung outside the houses. The mystery is partially solved, but it remains for many of those coming from the Middle Hills. Although I agree with Marc Petit’s view that anthropologists should dig into the memory of communities with an archaeological-like method in order to trace the origin of these masks, I fear results would be inconclusive.

NEPAL TODAY, A CHANGED WORLD More than 40 years have passed since these masks appeared on the markets in Kathmandu. Two generations have gone through sea changes: migrations to escape the terrible poverty of the mountains, improved transport and communications between mountains and urban centers, the connection to the electrical network, and the arrival of radio and television in largest villages. But also the civil war between Maoist guerrilla and government troops forced hundreds of thousands of refugees to leave their places of origin and consequently to lose the oral traditions that passed from one generation to the next. In the distant past the king was considered an incarnation of Vishnu and there was a court shaman; now the royal family is gone, wiped out by sweeping political and social tides.

Although grey areas still remain in our quest of knowledge for these masks, their power of attraction is unchanged. It is this magical allure which prompted Luciano Lanfranchi to assemble this collection with a sentiment that is perfectly articulated by Sam and Sharon Singer, “We are attracted to Himalayan masks because of the tribal artists’ ability to shape matter in a certain fashion and to infuse them with a personal vision. Looking at the Nepalese masks and figures means contemplating specimens of individual fantasy… Their system of beliefs, that mixture of Buddhism, Hinduism and animism, is instrumental to the understanding of the powerful craftsmanship and of the beauty of their artifacts.” It is the same sentiment expressed by many other passionate collectors and dealers, the one that sums up my own feelings and those of the people involved in this exciting narrative of Himalayan primitive masks. It is like looking at a group of characters: serious, nice, good-looking, horrible, aggressive, good-natured, zoned-out, threatening, ridiculous, mysterious, deep, absurd, a sort of Edgar Lee Masters’ masked Spoon River, even if we don’t know for certain who they represent.

Pingback:Indigenous Himalayan art is reaching new heights Apollo Magazine Emma Crichton-Miller | ETHNOFLORENCE INDIAN AND HIMALAYAN FOLK AND TRIBAL ARTS

Posted at 23:44h, 04 July[…] Link: https://www.renzofreschi.com/en/le-maschere-primitive-nepalesi-una-scoperta-unavventura-prefazione-d… […]