07 Nov THE SPIRIT RIDER

Village Heroes of Ancient India

by Renzo Freschi

The legend of the hero( the spirit rider) is universal and each culture shaped it according to its own history. In India the village hero always existed, since before the gods, ever since men and women identified themselves as a community and the community needed protection from whoever threatened it, be it man or beast. With him began the era of myth, but myth did not make of him an abstract figure, because his body is marked by wounds, stained with blood, sometimes defeated but more often victorious. Therefore his feats, passed on by word of mouth, have become immortal. Then the village became a city, and the city a nation, and the hero gradually lost his horse in favor of quite different weapons, but this does not concern the persons these bronze figures tell us about.

Images of the village hero’s cult exist in most of India, from Rajasthan -where stone slabs with the effigy of the knight fallen in battle tell the heroic feats of Rajput warriors – to the rural lands of Tamil Nadu -where we find the giant terracotta horses of Aiyanar, the protector god of the village and crops. However, the knight-hero is no secular figure in India, it rarely has a precise identity, often being considered a divine manifestation. As was always the case, new religions take over previous popular cults, and people like their heroes to become supernatural figures, their feats being inspired by divine grace.

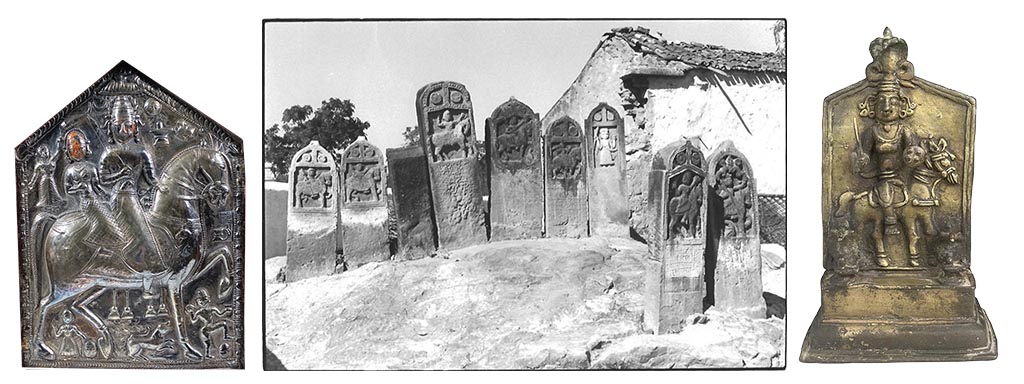

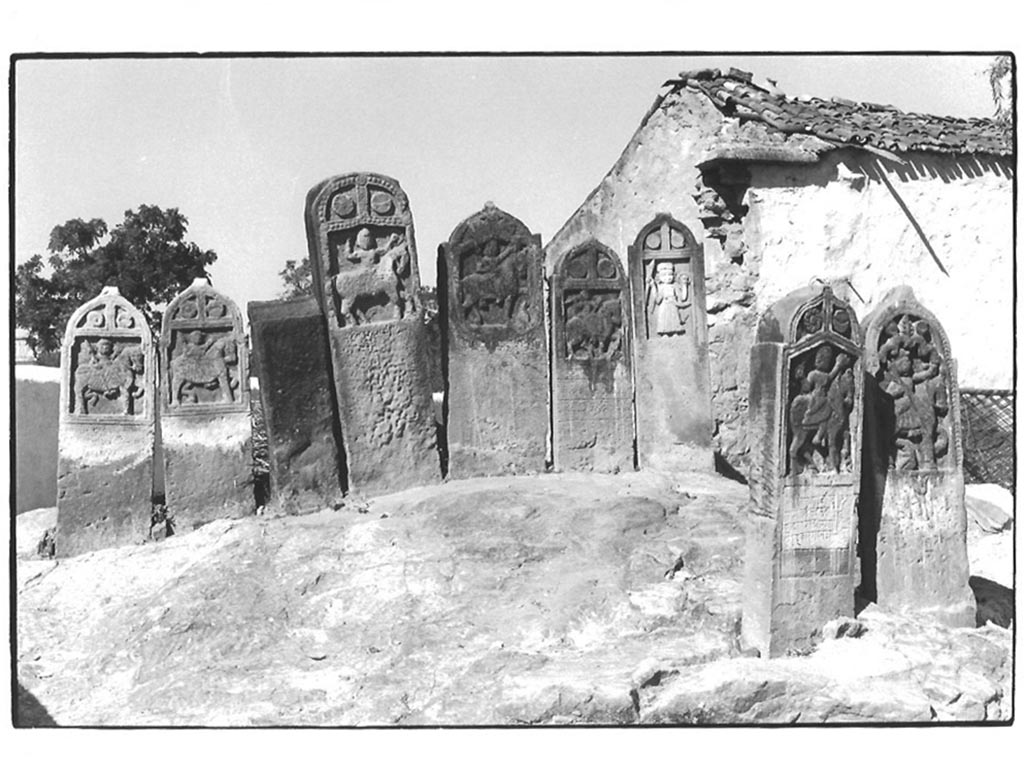

A group of commemorative steles.

Rajasthan 1983.

Photo Renzo Freschi

In India, through a process of “Hinduization”, the local hero becomes the incarnation of a god, not Brahma the creator and seldom Vishnu the preserver of order, but mainly of Shiva, a divinity tapping into the roots of myths and of folk cults and whose often martial appearance nicely suits the hero’s figure. Thus many of these bronze statues, in spite of their various names, are worshiped as manifestations of Shiva, and when the hero turns into a god his enemies become demons to be destroyed. The oldest figures on horseback date from the first centuries AD. They do not represent heroic knights but Hindu divinities like Indra, the king of gods, the first one riding a horse; then Surya, the sun god on a chariot driven by seven horses, and then Revanta, patron of hunters and protector of the spirits of the forest. For many centuries the images of these gods will adorn the temple walls; in a sense they are institutional images incorporating much older traditions. Only about the 15th century do the first bronze statues of riding heroes appear. It is hard to explain the lack of more ancient examples; probably the ancient cult of Viras, the ancestor-heroes, continued for centuries under the ecumenic wing of Hinduism, but around the 15th century historic events caused their cult to be renewed adding fresh and contemporary deified heroes. In the North the clash of the various Rajput kingdoms both among themselves and against the overwhelming Moghul invasion made of these warriors belonging to the kshatriya caste such indomitable and famous fighters that their heroic deeds migrated into folklore, celebrated by story-tellers and remembered by hundreds of memorial stelae in the places where they lost their lives. The knight then becomes a distinctive icon of the Rajput, and portraits of the maharaja and various princes riding a horse are quite popular.

In the 18th and 19th centuries the “horseback portrait” becomes a must which no aristocrat can elude, even though these are “political” paintings, in that they are aimed at celebrating personal power and have little to do with village heroes. In Rajasthan the cult of the knight-hero becomes so popular that his image is reproduced on silver medallions worn by women around the neck.

Also in Rajasthan members of the Bhil ethnic group manufacture small bronze horse riders (spirit riders) which, whilst similar in shape to those in the rest of India, do not belong to the knightly tradition but are considered “ferrymen” carrying the souls of the dead to the other world. These composed and stylized statuettes are used by the Bhils during funeral ceremonies. The cult of these heroic knights is so ubiquitous that it even spreads to vast areas of central India where the natives (adivasi) have always lived. Some ethnic groups such as the Kondhs and the Bastars manufacture metal knights aesthetically quite different from the sophisticated naturalism characterizing those of North and South India. The spontaneous simplicity of these statuettes turns them into conceptual images drawing on the roots of the community history. Proportions, finishing, details, the stiffness of horse and rider are not important, the idea of strength and archaic purity being much more relevant.

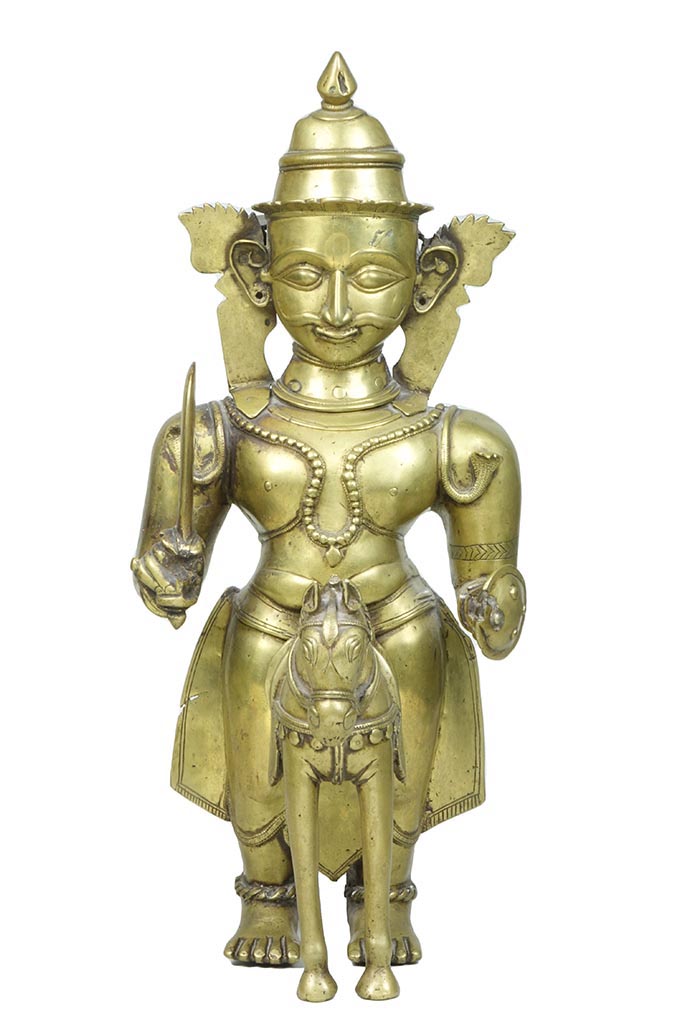

In South India too, from the 15th century onwards, the figure of the hero-knight becomes very popular, so much so that its image is placed in great temples and on home altars. The clash between the Moghul empire and the Hindu states is extremely violent and in the 17th century Shivaji, the ruler of the Maratha kingdom, manages to defeat the emperor Aurangzeb and save Deccan from the Islamic expansion. His figure of valiant leader, incarnating the village hero, becomes so famous that many bronze statues of knights probably constitute an unacknowledged celebration of it. In the South each region has its own brave leader in bronze, terracotta and wood, with different names: Khandoba, Karuppan Sami, Massanna, Aiyanar are originally local deities (grama devata) turned into manifestations of Shiva, seldom of Vishnu. It is often difficult to tell them apart since both Aiyanar and Khandoba wield a sword and shield. An important example of equestrian statues from South India are the two large bronze figures, one with a horse and the other without, made up of several parts which are assembled together and carried in procession during the annual festival dedicated to them. They wear the typical gear of a warrior with armor, helmet, sword and shield, but they are deified heroes, for the tambourine held by one and the two cobras on the other’s shoulders are Shiva’s attributes.

This combination of sacred and secular is frequent in Indian folk art; sometimes the personage remains undetermined and sometimes the four ritual objects identify him as Shiva. In some cases the warlike nature is apparent, since the knight high on his steed dominates the enemy who tries to defend himself with his sword but is attacked on the sides by the knight’s faithful dogs.

In the beautiful repoussé silver plaque victory over the enemy is made even more obvious by the severed heads under the horse’s hoofs. Khandoba and his female companion Mhalsa sit on a horse whose sheer size suggests the invincible strength of the leader.

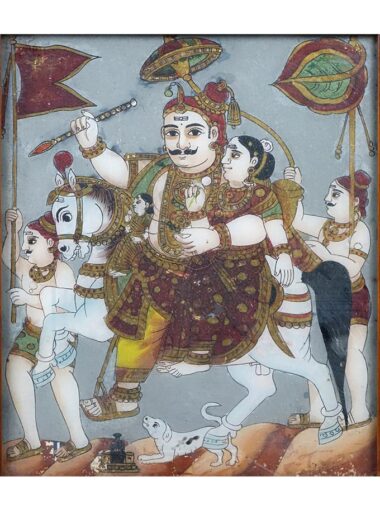

In some images from the South too the aspect celebrating aristocratic power prevails over the heroic or divine one (on the other hand are kings and emperors not considered divine figures all over the world?). The maharaja riding a sumptuously harnessed horse is flanked by two grooms carrying a flask and a bird, possibly preparing for a falcon hunt

Even more eulogistic is the painting on glass from the Tanjore school showing the maharaja together with wife and daughter on a rearing horse, preceded by an attendant carrying a banner and followed by a second servant holding a parasol over the king’s head.

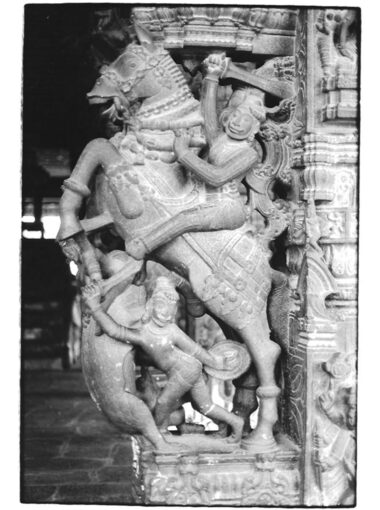

The figure of the riding hero also appears in the great shrines of Tamil Nadu, where the entrance columns of many temples are carved with magnificent riders and rearing horses, true masterpieces of Indian art and architecture.

The same applies to the colossal wooden processional chariots (ratha, moving temples really) decorated with openwork shelves showing rows of riders.

Times, customs, traditions change, but the figure of the heroic leader has not vanished from the country’s collective memory. Even nowadays, in most Indian marriages the bridegroom dressed up as a true leader still arrives on the site of the wedding ceremony riding a white horse.

No Comments